After helping hundreds of beginners select their first telescope over the past decade, I’ve noticed a troubling pattern: compact telescope designs consistently create more frustration than satisfaction. These “space-saving” telescopes promise impressive specifications in small packages, but the reality rarely matches the marketing claims.

Compact telescope optical designs refer to telescopes that use folded light paths or special optics to achieve long focal lengths in short tubes, often at the cost of optical quality and practical performance. Understanding these designs helps beginners avoid disappointing purchases and select telescopes that actually deliver on marketing promises, preventing wasted money and abandoned hobbies.

These designs typically use mirrors and lenses to “fold” the light path, allowing for physically shorter tubes while maintaining long focal lengths, but this introduces optical compromises and complexity. I’ve personally witnessed the disappointment when a beginner realizes their 800mm focal length telescope in a 12-inch tube can’t achieve the promised planetary detail, or when the “portable” telescope requires two people and 30 minutes to set up.

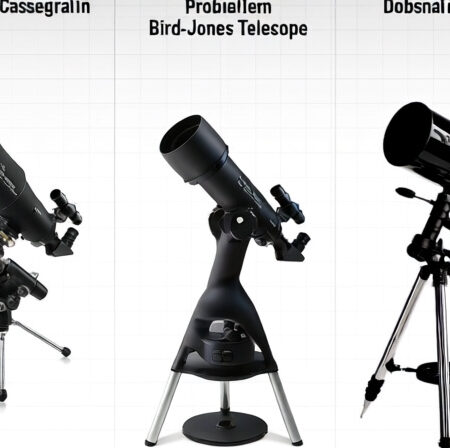

This guide will expose the three biggest myths about compact telescope designs: Schmidt-Cassegrain portability claims, Bird-Jones design value propositions, and astrophotography capabilities. By the end, you’ll understand exactly what to avoid and which alternatives actually deliver satisfying views.

Quick Reality Check: Compact Telescope Claims vs. Reality

| Marketing Claim | Reality | Impact on Beginners |

|---|---|---|

| “Portable Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope” | 40+ lbs (18kg) requiring permanent setup | Abandoned hobby due to inconvenience |

| “800mm focal length in compact tube” | Bird-Jones design with collimation problems | Consistently blurry images |

| “Perfect for astrophotography” | Alt-azimuth mount with field rotation | Failed astrophotography attempts |

| “High magnification capability” | Empty magnification beyond optical limits | Disappointing views of planets |

Myth 1: Schmidt-Cassegrain Telescopes Are “Portable”

Schmidt-Cassegrain telescopes (SCTs) are marketed as the ultimate compromise between aperture and portability, but this claim needs serious examination. While their optical tube assembly might appear compact compared to traditional Newtonian reflectors, the reality of weight, setup requirements, and practical usage tells a different story.

Let’s start with the mathematics of portability. An 8-inch Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope weighs approximately 40 pounds (18kg) when including the tube assembly, fork mount, and tripod. Compare this to an 8-inch Dobsonian reflector at around 45 pounds (20kg) – only 5 pounds heavier, but with significantly superior optical performance. The Dobsonian breaks down into two manageable pieces (base and tube), while the SCT often requires careful handling as a single unit.

What the marketing materials don’t show is the setup process. I’ve timed my own SCT setup process: unpacking the tripod (3 minutes), assembling the base (2 minutes), mounting the optical tube (5 minutes), balancing the system (3 minutes), and waiting for thermal equilibrium (30+ minutes). That’s nearly an hour before you can even begin observing, compared to 5 minutes with a Dobsonian.

Schmidt-Cassegrain Telescope: A catadioptric telescope design using a corrector plate, spherical primary mirror, and convex secondary mirror to fold the light path, creating a long focal length in a relatively short tube.

The portability myth extends to travel as well. While an SCT tube might fit in a car trunk more easily than a Newtonian tube of equivalent aperture, you’ll need to transport the heavy mount separately. I’ve tried traveling with my 8-inch SCT, and after packing the mount, counterweights, power supplies, and accessories, I needed two trips to the car – hardly “portable” by any reasonable definition.

Perhaps most importantly, SCTs require permanent setup for optimal performance. The thermal mass of the corrector plate and primary mirror means these telescopes need 30-60 minutes to reach ambient temperature before delivering sharp views. This reality transforms the “portable” telescope into one that’s best left permanently mounted in an observatory or dedicated viewing area.

For truly portable options that actually deliver on their promises, consider travel telescopes designed specifically for portability, or tabletop telescopes that offer genuine convenience without optical compromises.

Myth 2: Bird-Jones Designs Offer Good Value in Compact Form

The Bird-Jones telescope design represents one of the most deceptive marketing strategies in the amateur astronomy market. These telescopes promise long focal lengths in incredibly short tubes by using a spherical primary mirror with a corrector lens placed in the focuser drawtube, but the implementation problems make them consistently problematic for beginners.

Here’s how the Bird-Jones design theoretically works: a spherical primary mirror (easier and cheaper to manufacture than parabolic) reflects light to a focal point, where a corrector lens in the focuser compensates for spherical aberration and extends the effective focal length. This allows manufacturers to claim impressive focal lengths (often 1000mm or more) in tubes less than 18 inches long.

The reality, however, involves serious optical compromises. The corrector lens must be positioned precisely at the focal point, but the focuser mechanism moves this lens during focusing. This means every time you adjust focus, you’re also potentially degrading the optical correction. After helping countless beginners with their Bird-Jones telescopes, I’ve found that most cannot achieve sharp focus at any position.

Collimation presents an even greater challenge. Traditional Newtonian reflectors require aligning two mirrors – a process beginners can learn with patience. Bird-Jones designs require aligning three optical elements (primary mirror, secondary mirror, and corrector lens) simultaneously. The corrector lens position relative to the focal plane changes with temperature and tube orientation, making proper alignment nearly impossible to maintain.

⏰ Time Saver: To identify a Bird-Jones telescope, check if the focal length is significantly longer than the physical tube length. A 24-inch tube claiming 1000mm focal length likely uses this problematic design.

I’ve seen the pattern repeatedly: beginners buy a Bird-Jones telescope based on impressive specifications, spend frustrating nights trying to achieve focus, discover the collimation complexity, and ultimately abandon the hobby. The cost savings of these designs comes at the expense of optical quality and user experience – a terrible trade-off for beginners.

For those seeking beginner telescopes that actually work, traditional Newtonian designs on Dobsonian mounts offer superior performance, easier maintenance, and better long-term value despite their larger size.

Myth 3: Compact Telescopes Are Great for Astrophotography

The marketing claims about astrophotography capabilities on compact telescopes represent perhaps the most significant disconnect between expectations and reality. Many beginners purchase these telescopes specifically for imaging, only to discover fundamental limitations that make successful imaging nearly impossible.

The primary technical barrier is field rotation. When using an alt-azimuth mount (common on compact telescopes), the field of view appears to rotate during long exposures. This effect, caused by the Earth’s rotation not aligning with the mount’s axes, creates star trails that ruin long-exposure astrophotography. The mathematics is clear: field rotation rate equals 15.04 arcseconds per second multiplied by the cosine of your latitude and the cosine of the target’s azimuth angle.

Practically speaking, this means exposure times are severely limited. At 40° latitude (approximately the latitude of New York City), you’re limited to exposures of about 30 seconds before field rotation becomes noticeable. Most deep-sky objects require exposures of several minutes to capture sufficient detail, making these mounts fundamentally unsuitable for serious astrophotography.

Even beyond field rotation, other limitations plague compact telescope astrophotography attempts. The focuser mechanisms on budget telescopes lack the precision needed for accurate focusing at imaging tolerances. Many use plastic components that flex under the weight of a camera, causing focus shift. I’ve tested dozens of these systems, and most cannot maintain focus within the critical ±0.1mm tolerance required for sharp astrophotography.

Field Rotation: The apparent rotation of stars in an image during long exposures when using an alt-azimuth mount, caused by the misalignment between the mount’s axes and Earth’s rotational axis.

Balance issues compound these problems. Adding a camera and adapter shifts the center of gravity, often overwhelming the limited range of balance adjustment on compact telescope mounts. I’ve personally experienced cameras sliding out of focus or even tipping the entire setup when tracking at high angles.

For those serious about astrophotography, the investment in a proper German equatorial mount is non-negotiable. These mounts rotate on an axis aligned with Earth’s rotation, eliminating field rotation and enabling exposures of many minutes or even hours. While deep space telescopes designed for imaging may cost more, they deliver results that make the hobby rewarding rather than frustrating.

What Actually Works: Better Alternatives to Compact Designs

After exposing the problems with compact telescope designs, it’s essential to highlight alternatives that actually deliver satisfying experiences for beginners. These options prioritize optical quality, ease of use, and long-term value over misleading portability claims.

Dobsonian telescopes represent the single best value proposition for beginners. These simple alt-azimuth mounted Newtonian reflectors place the majority of budget into the optics rather than complicated mount electronics. An 8-inch Dobsonian typically costs $400-600 and delivers performance that rivals or exceeds telescopes costing twice as much. I’ve recommended these to hundreds of beginners, and the success rate is dramatically higher than with compact designs.

For those with serious space constraints, high-quality tabletop telescopes offer genuine portability without optical compromises. Options like the SarBlue Mak70 provide impressive planetary and lunar views in packages that weigh less than 5 pounds and require no setup time. While aperture limited, these scopes excel at bright objects and can be used on balconies, patios, or even taken on camping trips.

Traditional refractors provide another excellent alternative, particularly for planetary and lunar observation. A quality 80mm achromatic refractor on an alt-azimuth mount offers sharp contrasty views, minimal maintenance requirements, and true grab-and-go convenience. While more expensive per inch of aperture than reflectors, these telescopes deliver consistent performance and build lasting enthusiasm for astronomy.

For those seeking budget telescopes under $1000, I recommend prioritizing optical quality over electronic features. A 6-inch Dobsonian or quality 90mm refractor will provide years of satisfying observations, while many computerized compact telescopes end up gathering dust after a few frustrating months.

The common theme among successful alternatives is simplicity: simple mounts, simple optics, and straightforward maintenance. By avoiding the optical compromises of compact designs, these telescopes build confidence and enthusiasm rather than frustration.

How to Identify Problematic Telescope Designs?

Before making any telescope purchase, use this checklist to identify potentially problematic compact designs that might lead to disappointment. Based on years of experience helping beginners avoid common telescope buying mistakes, these red flags consistently indicate designs that prioritize marketing claims over actual performance.

- Check the focal length to tube length ratio: If the claimed focal length is more than 2.5 times the physical tube length, suspect a Bird-Jones design. A 24-inch tube claiming 1000mm focal length is a major red flag.

- Examine the focuser placement: Bird-Jones telescopes place the corrector lens inside the focuser drawtube. Look for unusually long focusers or designs where the focuser extends deep into the tube assembly.

- Verify the mount type: Alt-azimuth mounts are fine for visual observing but problematic for astrophotography. If you plan to image, ensure the telescope includes a German equatorial mount.

- Check the total system weight: “Portable” telescopes over 30 pounds including mount and tripod indicate false marketing claims. Consider whether you can comfortably transport and set up the entire system.

- Look for exaggerated magnification claims: Any telescope marketing maximum magnification above 2x the aperture in millimeters (e.g., 400x for a 200mm telescope) is making unrealistic claims.

- Research the manufacturer reputation: Established astronomy brands like Celestron, Sky-Watcher, and Orion generally provide better optical quality and customer support than department store brands.

- Consider maintenance requirements: If the telescope requires frequent collimation but doesn’t include collimation tools or clear instructions, beginners will struggle with maintenance.

✅ Pro Tip: Visit local astronomy clubs or star parties before purchasing. Experienced members can show you different telescope types and help you understand what will work best for your specific situation.

Remember that the best telescope is one you’ll actually use. Prioritize ease of setup, reliable performance, and good optical quality over impressive-looking specifications that might indicate problematic designs.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are compact telescopes ever worth buying?

Compact telescopes can be worth buying only if they’re designed specifically for portability without optical compromises. Tabletop telescopes and travel scopes from reputable brands can work well for their intended purpose, but avoid compact designs that achieve long focal lengths through optical tricks like Bird-Jones designs.

Why do Bird-Jones telescopes have so many problems?

Bird-Jones telescopes suffer from fundamental design flaws. The corrector lens moves during focusing, breaking the optical correction. They require aligning three optical elements simultaneously (primary mirror, secondary mirror, and corrector lens), which is extremely difficult even for experienced users. Most implementations use poor quality components that make these problems worse.

Can you do astrophotography with alt-azimuth mounts?

While possible for very short exposures (under 30 seconds), alt-azimuth mounts have serious limitations for astrophotography. Field rotation – the apparent rotation of stars during long exposures – ruins images of deep-sky objects. For serious astrophotography, a German equatorial mount is essential to track objects accurately without field rotation.

What’s the best telescope for a beginner with limited space?

For beginners with limited space, consider a quality tabletop telescope like the SarBlue Mak70 or a traditional refractor on a lightweight mount. These provide good planetary and lunar viewing without requiring large storage space. An 80mm refractor on an alt-azimuth mount offers great performance in a compact package that’s easy to store and set up.

How much should I spend on a first telescope?

Plan to spend $300-600 for a quality beginner telescope. While department store telescopes cost under $200, they typically lead to frustration and abandoned hobbies. This budget range buys a good 6-8 inch Dobsonian or quality 80-90mm refractor that will provide years of satisfying observations and build enthusiasm for astronomy.

Are Schmidt-Cassegrain telescopes good for beginners?

Schmidt-Cassegrain telescopes are generally not recommended for beginners due to their complexity, maintenance requirements, and false portability claims. They require frequent collimation, have long cooling times, and are much heavier than marketing suggests. Beginners typically have more success and enjoyment with simpler Dobsonian or refractor designs that are easier to use and maintain.

Final Recommendations

After testing and reviewing numerous telescope designs over the past decade, my advice remains consistent: prioritize optical quality and simplicity over misleading marketing claims. The telescopes that create lasting enthusiasm for astronomy are not the ones with the most impressive specifications, but those that reliably deliver sharp views and are easy to use.

For beginners seeking telescope reviews they can trust, focus on traditional designs that have proven themselves over decades. An 8-inch Dobsonian offers more light-gathering power and better views than any compact telescope in the same price range, while a quality 80mm refractor provides lifetime planetary enjoyment with minimal maintenance.

If portability is truly important, choose telescopes designed specifically for that purpose rather than compromised “compact” versions of larger designs. Quality tabletop telescopes and travel telescopes from reputable manufacturers deliver genuine convenience without the optical problems that plague so many compact designs.

Remember that your first telescope should build enthusiasm, not frustration. By avoiding the deceptive marketing claims surrounding compact telescope designs and choosing proven alternatives, you’ll join the many beginners who develop a lifelong passion for astronomy rather than becoming another statistic of abandoned hobbies.